In a previous article, we discussed Curiefense’s tag-based real-time traffic processing:

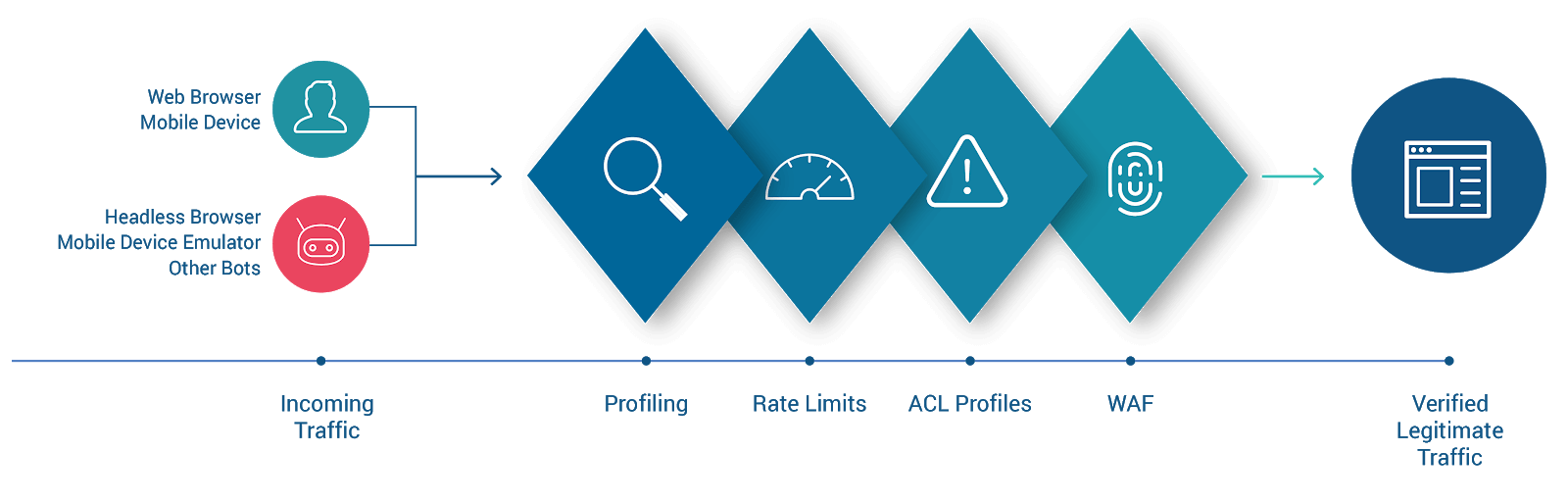

In the diagram, requests enter from the left and proceed through several stages of evaluation. Those which do not violate any security policies or otherwise exhibit anomalous behavior are allowed through to the protected web resource on the right.

The last stage of evaluation is the WAF. In the previous article, this was discussed briefly; in this article, we’ll take a closer look.

WAF is an acronym for Web Application Firewall. Often this term is used rather broadly (and imprecisely) to describe a security solution that performs various types of traffic filtering. We’ll use the term here in its narrower, more precise sense: a firewall that blocks malicious HTTP requests.

Curiefense’s WAF protects against a wide range of attacks: SQL injection, code and command injection, directory traversals, file access attempts, cross-site scripting (XSS), and more. It can detect any malicious activity which can be discerned by inspecting an individual request and its contents (its headers, arguments, etc.)

Traditionally, WAFs have been used to protect sites and web applications. Curiefense’s WAF can also protect services and APIs, and offers the same set of capabilities for them as it does for sites and apps.

Curiefense includes an extensive and regularly-updated database of threat signatures. By default, it filters every incoming request that matches a signature. However, it is possible to exempt requests from evaluation against one or more specific signatures.

Here’s an example of why this can be useful. When an incoming HTTP request has a parameter that contains an apostrophe, this usually indicates an attempt at SQL injection. Therefore, Curiefense includes a threat signature that will block this request. However, in some situations, an apostrophe might be valid within certain input parameters. Thus, an administrator can configure Curiefense to exempt those parameters from being evaluated against that signature.

In addition to these built-in threat signatures, Curiefense users can create a wide variety of additional filters. This includes content filtering; users can supply regex patterns which define the allowable structure and content of request parameters.

This capability can be quite powerful. A request that does not match these custom filters can be blocked automatically, or subjected to further scrutiny, depending on the configuration.

Curiefense’s WAF policies are combined into WAF Profiles, which can be assigned to any scope of paths/URLs within the protected web service. In a typical deployment, there will be a few specific Profiles customized for individual URLs, several additional Profiles for broader paths, and one that applies by default to every URL not otherwise specified.

That’s the Curiefense WAF in a nutshell. In the remainder of this article, we’ll discuss its traffic filtering in more detail.

Curiefense uses both negative security and positive security models:

Each model has strengths and weaknesses. For example, negative security cannot protect against zero-days, while positive security has a higher risk of producing false-positive alarms. Therefore, Curiefense uses both, to leverage their advantages while avoiding their disadvantages. Here’s how it does this.

As mentioned above, Curiefense includes an extensive database of threat signatures. They are viewable in the UI, as shown in the following example. (This particular one detects a specific type of SQL injection.)

By default, a request which matches any of the threat signatures will be blocked. (This is part of Curiefense’s negative security model.)

Additional security policies can be defined by administrators. Some of these also use negative security, such as enforcement of maximum limits for the length and number of headers, cookies and arguments.

Other policies use positive security, such as those which define the allowable content of specific parameters (headers, cookies, and/or arguments). Requests which do not match these policies can be blocked.

Some policies use a hybrid approach. For example, regex patterns can be defined for specific parameters, and used as follows:

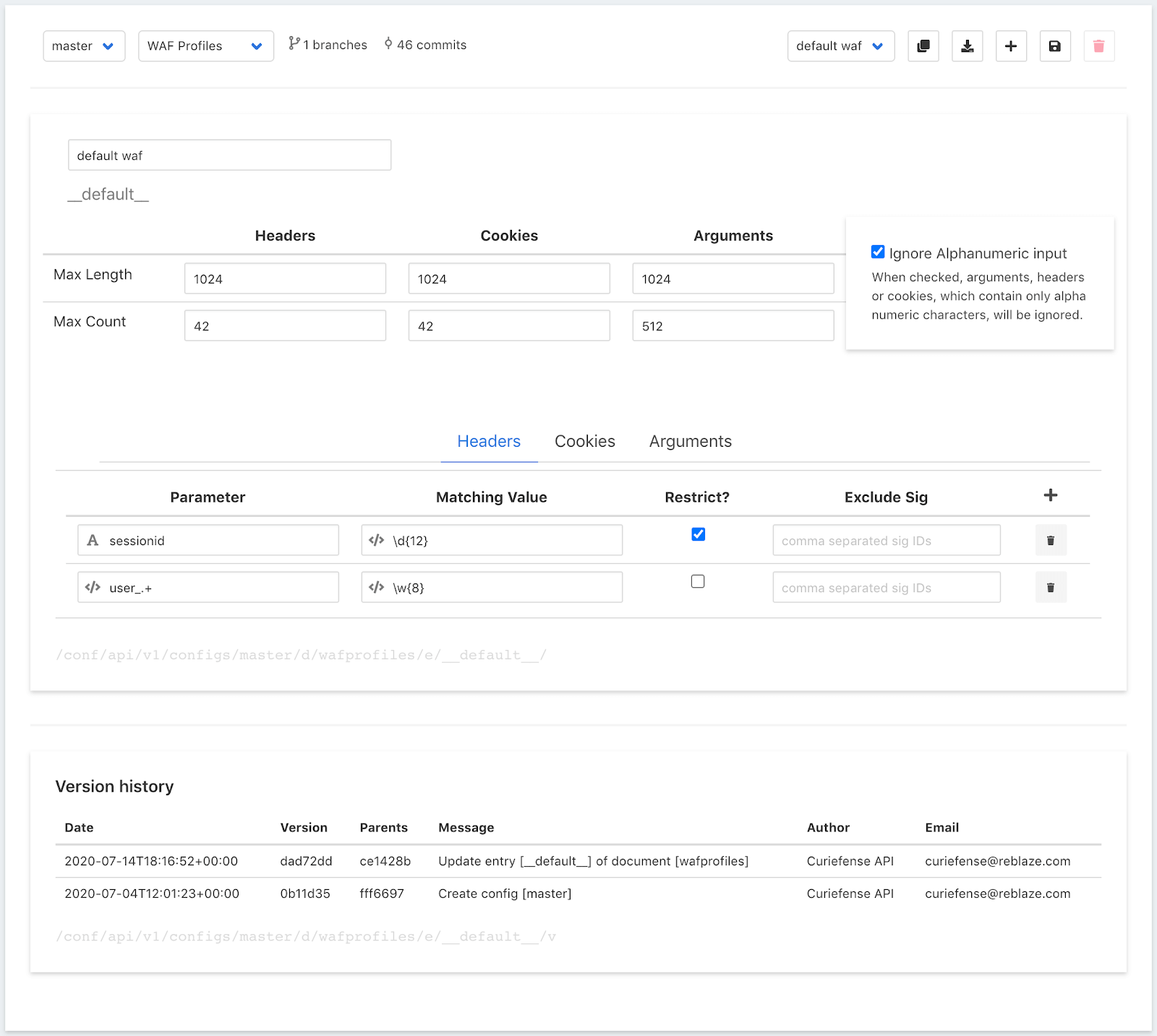

To illustrate this, here’s a sample set of WAF security policies (known as a WAF Profile) in the Curiefense UI:

If this Profile were active for a URL, and an incoming request was received for that URL, Curiefense would iterate through all of the request’s parameters—through every header, cookie, and argument—and evaluate each one as follows:

Note that Curiefense allows the above processing to be bypassed if desired. The “Ignore Alphanumeric Input” option instructs the WAF to treat parameters as benign if they contain only alphanumeric characters. This saves processing time, and it can be useful in situations where extensive content filtering is not needed.

For more information on configuring the Curiefense WAF, see the documentation.

As shown in the UI screenshot, individual filter rules are combined into a WAF Profile. Profiles can be assigned to paths throughout the protected web service, from globally down to individual URLs. Paths can be specified using regex, which makes it straightforward to administer even complicated deployments.

Lastly, as with every other type of configuration within Curiefense:

A WAF processes requests, and filters them based on their contents. Many attacks are out of scope for WAF filtering, because the individual requests themselves seem benign. For example, a credential stuffing attack consists of requests that are not overtly malicious—they contain no injection attempts, no attempts to access system files, and so on.

Curiefense can handle those types of attacks as well, because it has a robust set of threat detection capabilities that go far beyond WAF filtering. We’ll discuss those capabilities in future articles.