Another high-profile breach is in the news; this time, the victim was compromised through Slack. Here’s what happened, and how Curiefense can help to avoid a similar incident at your organization.

The victim was Electronic Arts (EA), the publisher of many popular games including Battlefield, Madden, The Sims, FIFA, and others. On June 6, hackers penetrated EA’s systems and stole source code for FIFA 21, the Frostbite engine, a variety of tools and SDKs, and more. All told, the attackers exfiltrated about 780 Gb of data, and they’re now offering it for sale on underground markets.

The attackers have provided some information about how the hack was done. Here are the three main stages of the incident:

This allowed the attackers to log in successfully. At this point, the attackers had penetrated EA’s perimeter and could move around inside with a fair degree of freedom. After a few more steps, they were able to access a developer’s service and download source code.

Each of the three stages exploited a different vulnerability at EA. And each one is worth discussing, because your organization might also have one—or even all—of these same vulnerabilities.

Let’s start with the last stage: the social engineering attack that converted Slack access into network access. Presumably, the hapless IT admin who generated the login token was not following correct procedures. In a situation like this, IT should have verified the user’s identity with some sort of multifactorial approach. For example, rather than providing a token, perhaps the admin could have sent a reset link to the user’s company email address.

The first lesson of the EA breach is that social engineering attacks can be very convincing. If an IT admin can be fooled—a person who should be knowledgeable about social engineering techniques, and is supposed to be suspicious of unusual requests like this—how much easier would it be to trick other team members?

This incident is a reminder that staff members need to be well-informed about these attacks, with frequent refreshers. “We had a training session about that once” is not sufficient; people need regular reinforcement about this subject. (Incidentally, the EA breach creates a great opportunity for this. It’s a recent, prominent incident that illustrates how badly things can go wrong when proper procedures are not followed.)

Having said all that, the third-stage social engineering attack couldn’t have happened if the first two stages hadn’t been successful. These too are worth discussing, because they exploited common vulnerabilities: vulnerabilities that your organization might also have, but which Curiefense can help defend against.

Before discussing them individually, let’s talk about the overall structure of the attack.

The EA breach began with session hijacking, which is a very popular attack today. When a user’s session is hijacked, the attacker can, in a sense, become the user; as far as the web application is concerned, the attacker has the exact same identity, access, and privileges as the user.

Session hijacking techniques abuse the stateless nature of the HTTP protocol. HTTP provides no inherent way to create and maintain sessions; each request is independent and stands alone. However, sessions are an important part of the user experience. For example, when bank customers access their accounts through a web application, they would rather not provide login credentials with every action they take.

Thus, a typical approach is for the server to create a unique session token (e.g., a randomly-generated string) at the beginning of a new session. The token is sent to the user’s browser, which stores it client-side (commonly, as a cookie), and includes it with all subsequent requests. This is how the server can associate each incoming request with a specific user.

The problem with this system is that it assumes that the session tokens are maintained securely. If an attacker gains access to a session token, then the attacker can send requests to the server with that token, and hijack the identity of the user within that session.

With this background established, let’s discuss the first two stages of the EA breach.

Insecure session tokens are the first vulnerability that was exploited in this attack. If the cookies weren’t available to the hackers, this attack would not have been possible.

Currently, it’s not publicly known which cookies were stolen and used in this event. (Slack can authenticate its users in several ways, including third parties such as Google and Apple.) But for this discussion, the relevant question is whether or not the users of your applications can have their cookies accessed by an attacker.

Unfortunately, it’s impossible to prevent this with 100 percent certainty. If a user’s machine is compromised, then a skilled hacker can exfiltrate their user credentials by installing a keylogger, and/or can steal their cookies via techniques such as a Man in the Browser attack.

Nevertheless, that’s difficult for attackers to accomplish, and other methods of session hijacking are far more common. And there’s much that you can do to prevent these.

Session hijacking is a broad and complex topic, but in general, there are three requirements for securing cookies.

Curiefense can help with the latter two points, and automate much of this process. It can enforce TLS on all incoming traffic automatically, including for APIs.

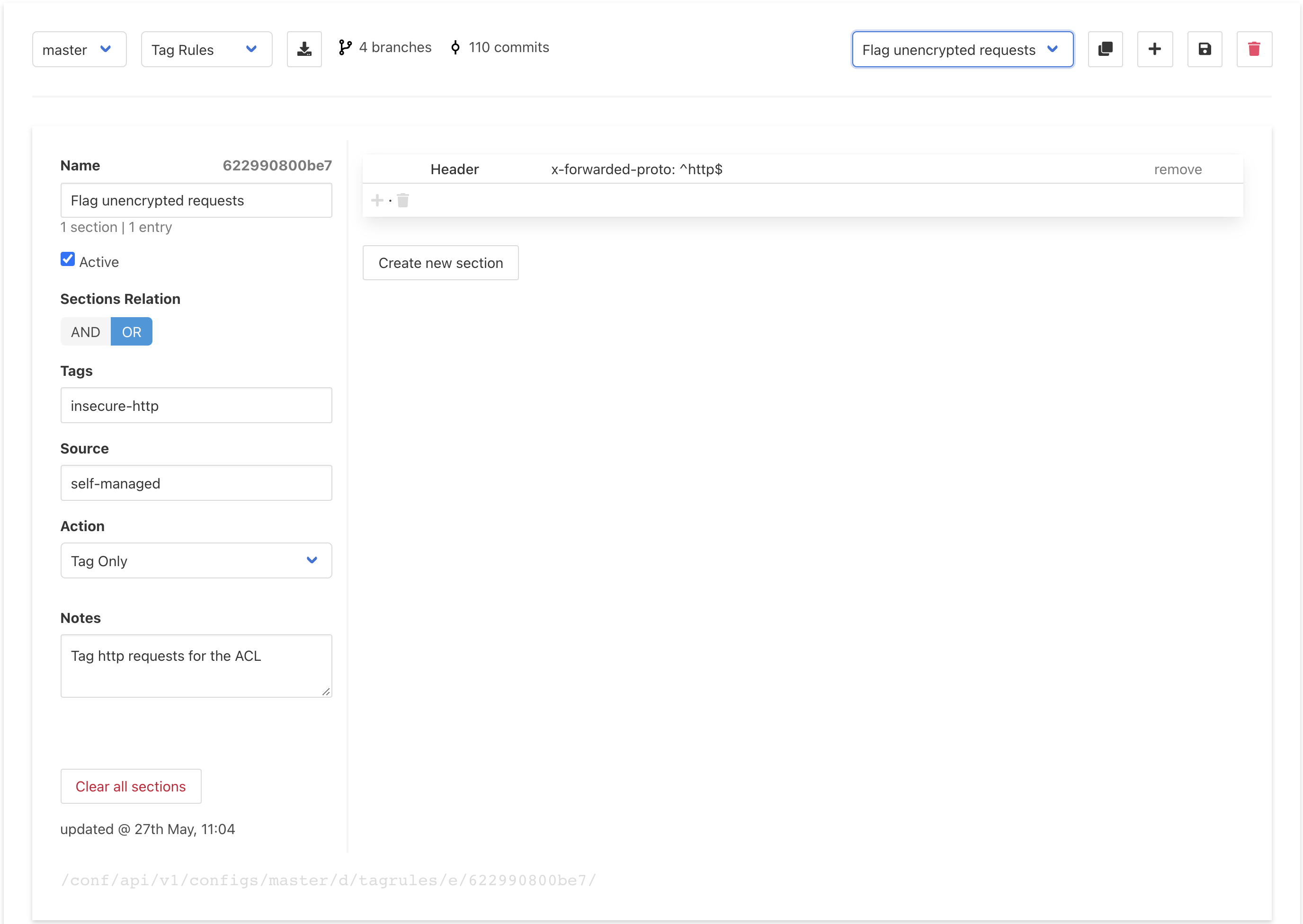

Here’s one way this can be done. First, all insecure traffic is tagged by a Tag Rule:

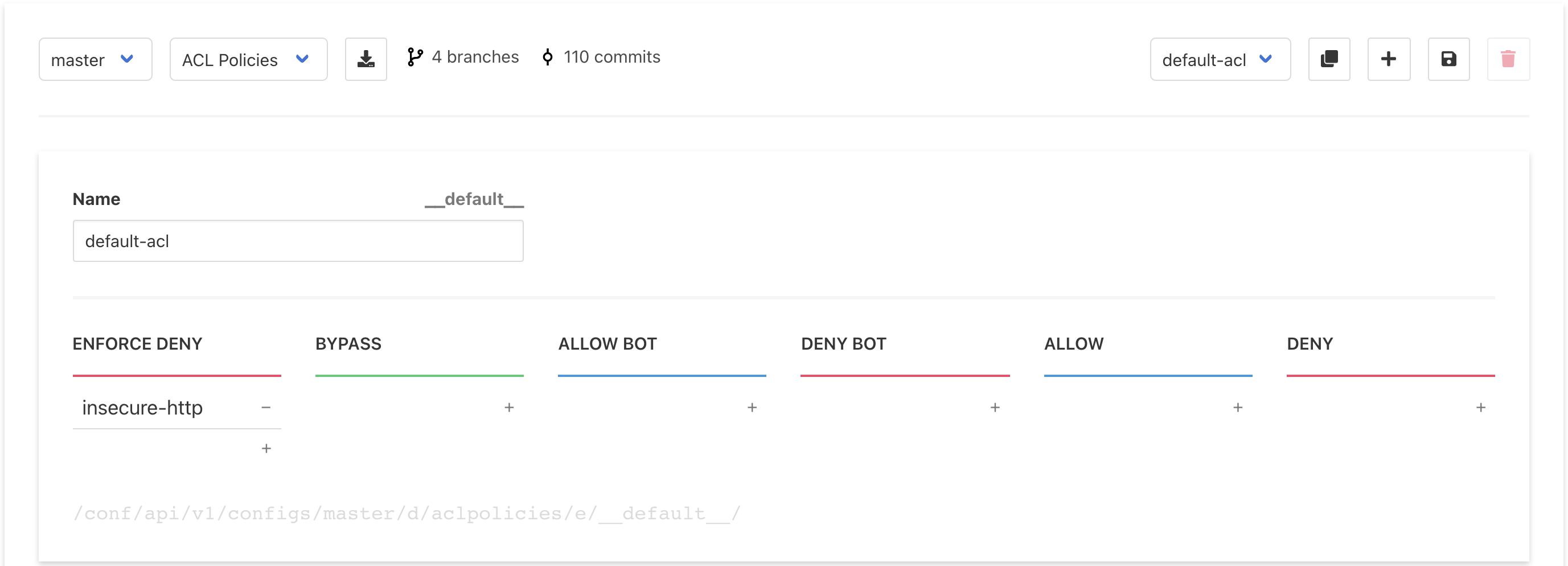

And then all requests with that tag are blocked by this ACL Policy:

If you make your users’ cookies unpredictable, unsettable, and unsniffable, it will be very difficult for attackers to obtain session tokens. But you should still prepare for the possibility that a user’s cookies get compromised anyway. And this brings us to the next stage of the EA attack.

Once session tokens are obtained, they must be used. Obviously, the EA attackers were able to do this successfully.

Thus, failure to prevent token abuse is the second vulnerability exploited in this event. To avoid this, your system must try to make stolen tokens worthless to the attacker.

There are several different approaches for doing this. They are not mutually exclusive, and ideally, your system would be doing all of them. Here they are, in order of increasing difficulty.

The last tactic is important, but there are two caveats. First, some organizations are hesitant to do this, for fear of inconveniencing their users (who will occasionally be asked to re-authenticate themselves during a legitimate session). However, users today are becoming accustomed to this, since many sites (banks, webmail providers, and so on) are adopting shorter default durations for their sessions. When compared to the possibility of a breach, this slight potential inconvenience isn’t significant.

Second, monitoring session context is not necessarily easy to implement for many environments. However, this can be done with a solution such as Curiefense.

For example, when a new user attempts to connect to a Curiefense-protected system, its bot management module runs a number of checks (which are invisible to the user) to verify that this is a human, and not a hostile bot. This includes identification of a number of characteristics, such as geolocation, browser environment, and much more; as it turns out, these are also very useful for detecting a session attack, since they are unlikely to all change simultaneously during a legitimate session.

Since Curiefense already monitors these parameters, it’s straightforward to set up security policies that will trigger when one or more of them change. Admins can set up different responses, depending on the magnitude of the change.

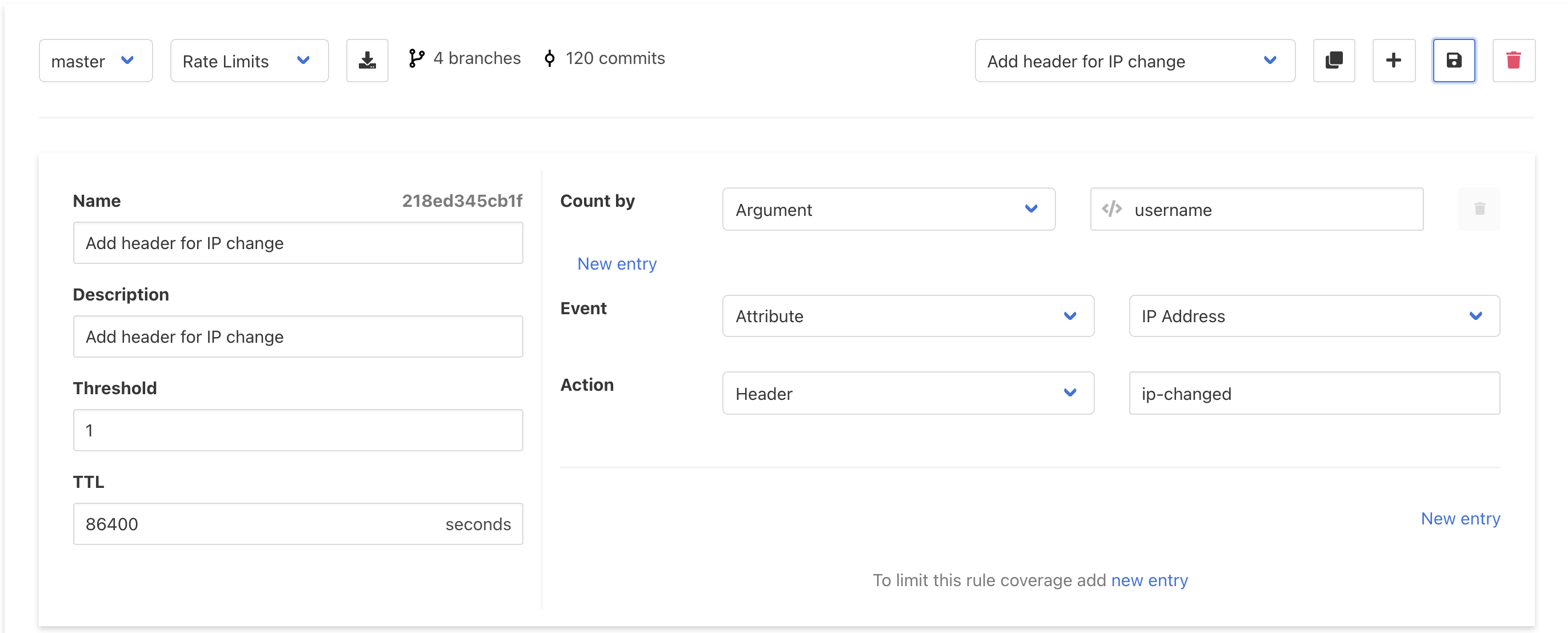

For example, here’s a Rate Limit rule that’s configured for sessions with maximum durations of 24 hours. If a user changes its IP during a session, Curiefense will add a custom header (ip-changed) to the request, notifying the upstream server so it can ask the user to re-authenticate.

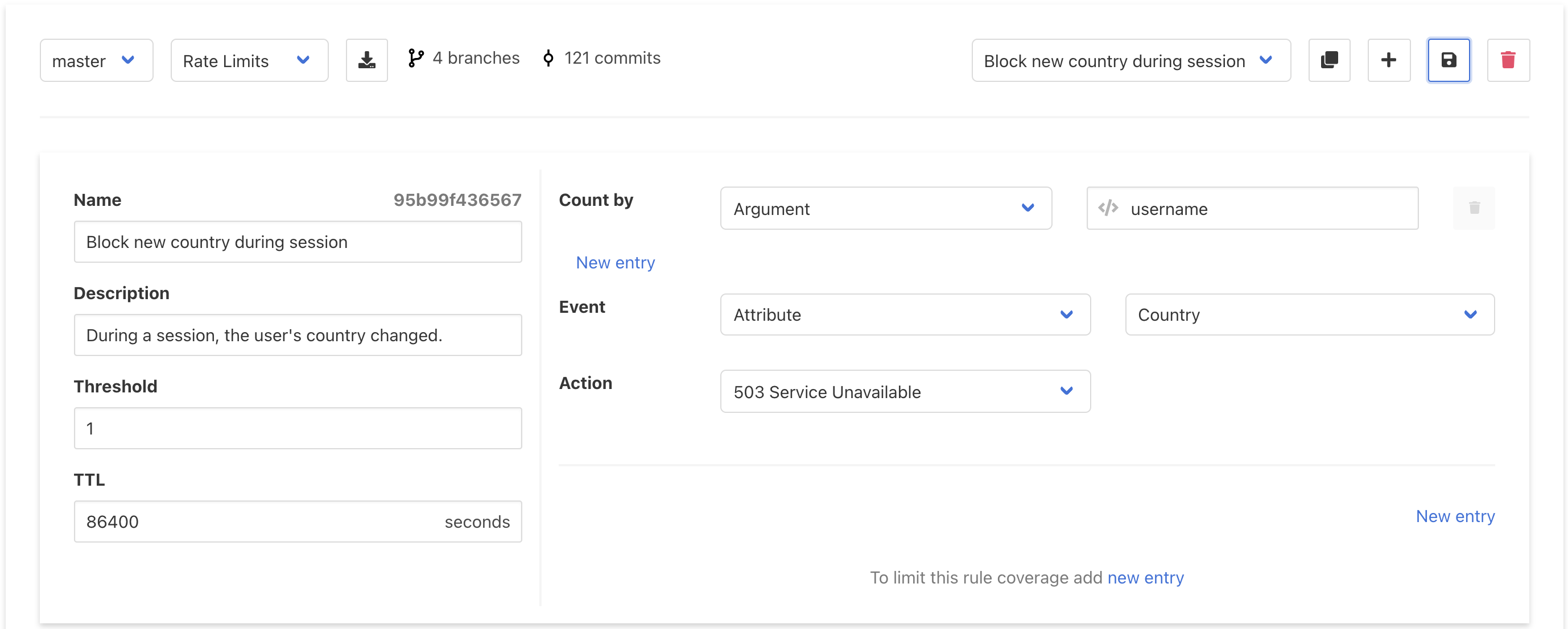

However, in other situations where the context changes more drastically, an admin might want a stricter response. The following rule will detect when the user’s country changes, and will block all subsequent activity until the session has had time to expire.

The Electronic Arts breach was a sophisticated, multi-vector attack. One vector exploited deficiencies in training and/or compliance among EA’s IT staff, while the other two vectors exploited technical vulnerabilities.

This incident highlights the growing complexity of modern web threats. Defending against them requires a sophisticated solution built on leading-edge security technologies. Fortunately, Curiefense provides a variety of tools and techniques to help prevent session hijacking.

Photo credit: Markus Spiske via unsplash